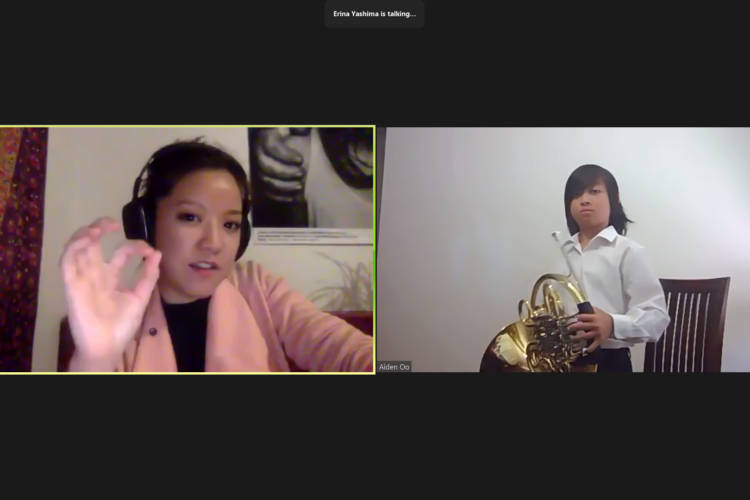

Erina Yashima joined PIMF in a virtual all-instruments Master Class in February that showcased her wide-ranging expertise, generous guidance, and astonishing energy. She is currently Assistant Conductor of the Philadelphia Orchestra and joined us from Germany, where she focused with laser precision and good cheer for two hours starting in the wee hours of the morning!

If you’d like to get all the insights from our upcoming Master Classes in real time, be sure to check out the Spring Series, which is complimentary to music students and educators.

In the meantime, we’ve distilled some of Erina Yashima’s thoughts that can be applied to almost any music practice and performance.

- She urged Aiden Oo of Australia to sing the phrases of the piece out loud himself in his preparation to play them on the French horn, to feel the shape and literally give voice to the musical conversation. Maestra Yashima feels this is especially useful in repeated phrases of music, explaining that there’s always a reason a composer repeats a phrase and perhaps even embellishes it: “Find the reason, and the expression will follow.”

- Speaking to harpist Emily Fowler of Indiana, Maestra Yashima advised against rushing the “small notes,” even if it’s done smoothly: “Give each note its importance!” She also urged giving notes a little more space to underline them at the peak of an arpeggio.

- Making each note distinct ties in to what she calls “audience empathy” in great performers: “Consider that you might be playing in a big hall with a lot of echo, a lot of reverb, people not sitting close to you like in a chamber hall or rehearsal space. In the COVID times we tend to forget the need to project in an open space and how different the music sounds in the back of the hall, especially to people hearing a piece for the first time.”

- Maestra Yashima used baseball to illustrate the importance of not throwing a curveball to the orchestra or accompanist, describing a last-second gust of wind changing a falling baseball’s direction as it approaches the catcher’s mitt: “When a rubato is not predictable in the sense that it is organic and leading into something, it’s like that sudden gust of wind. So always be conscious of it because you have to be together with the orchestra, so help them with the right impulse while you play.”

- Studying, analyzing, and knowledge underpin her preparation for any piece to conduct: “Behind every decision there has to be absolutely something that can’t be planned, a decision that grows from passion, from a deeper level. You have to fill that with a strong sense for timing, for feeling, for dramatic moments – and there are all kinds of things. The more time you spend with a piece, to digest it, the more it will be a part of yourself and the more the interpretation will come from a deeper part of yourself.”

Advice to someone auditioning for a professional orchestra: When you audition, imagine you are playing for one person. “Not a general, anonymous committee behind the curtain but for a friend,” someone important to you, to whom you have something important to communicate. “And be as concrete as possible in addressing what you want to say, not like an official announcement of something, but so that (your music-making) has a direct connection to a person.”